Background information and definitions

Definition: ‘Large adjoining cavities or ‘swimthrough’ habitats’ are adjoining internal cavities sheltered from, but with access to/from, outside the structure. Dimensions can vary but are >100 mm in any direction.

Large adjoining cavities or ‘swimthrough’ habitats are not well-studied in intertidal rocky habitats. They may form through weathering of softer rocks, amongst loosely-consolidated boulders, or within three-dimensional structures created by living organisms. They likely provide organisms refuge from desiccation, temperature fluctuations and predation, in the same way crevice, hole and rock pool habitats do (Menge & Lubchenco 1981; Williams & Morritt 1995). They could also serve as corridors, connecting adjacent refuge habitats. The size and density of cavities or swimthroughs is likely to affect the size, abundance and variety of organisms that can use them. Small habitats can provide refuge for small-bodied organisms but may exclude larger organisms, limit their growth and get rapidly filled-up (Firth et al. 2020). Large habitats can be used by larger-bodied organisms but may not provide sufficient refuge from predators for smaller organisms. By default, cavities and swimthroughs contain shaded surfaces, which can be associated with the presence of non-native species (Dafforn 2017).

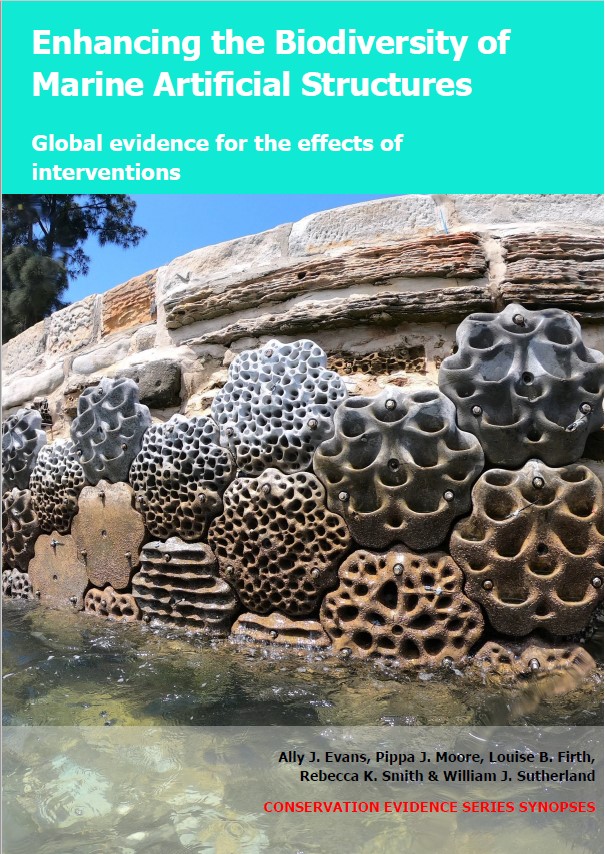

Cavities/swimthroughs are sometimes present on marine artificial structures made of consolidated boulders or blocks (Sherrard et al. 2016) or gabion baskets (Firth et al. 2014), but are absent from many other structures. Large adjoining cavities or ‘swimthrough’ habitats can be created on intertidal artificial structures by adding or removing material, either during construction or retrospectively.

See also: Create hole habitats (>50 mm) on intertidal artificial structures; Create crevice habitats (>50 mm) on intertidal artificial structures; Create ‘rock pools’ on intertidal artificial structures; Create small adjoining cavities or ‘swimthrough’ habitats (≤100 mm) on intertidal artificial structures.

Dafforn K.A. (2017) Eco-engineering and management strategies for marine infrastructures to reduce establishment and dispersal of non-indigenous species. Management of Biological Invasions, 8, 153–161.

Firth L.B., Airoldi L., Bulleri F., Challinor S., Chee S.-Y., Evans A.J., Hanley M.E., Knights A.M., O’Shaughnessy K., Thompson R.C. & Hawkins S.J. (2020) Greening of grey infrastructure should not be used as a Trojan horse to facilitate coastal development. Journal of Applied Ecology, 57, 1762–1768.

Firth L.B., Thompson R.C., Bohn K., Abbiati M., Airoldi L., Bouma T.J., Bozzeda F., Ceccherelli V.U., Colangelo M.A., Evans A., Ferrario F., Hanley M.E., Hinz H., Hoggart S.P.G., Jackson J.E., Moore P., Morgan E.H., Perkol-Finkel S., Skov M.W., Strain E.M., van Belzen J. & Hawkins S.J. (2014) Between a rock and a hard place: environmental and engineering considerations when designing coastal defence structures. Coastal Engineering, 87, 122–135.

Menge B.A. & Lubchenco J. (1981) Community organization in temperate and tropical rocky intertidal habitats: prey refuges in relation to consumer pressure gradients. Ecological Monographs, 51, 429–450.

Sherrard T.R.W., Hawkins S.J., Barfield P., Kitou M., Bray S. & Osborne P.E. (2016) Hidden biodiversity in cryptic habitats provided by porous coastal defence structures. Coastal Engineering, 118, 12–20.

Williams G.A. & Morritt D. (1995) Habitat partitioning and thermal tolerance in a tropical limpet, Cellana grata. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 124, 89–103.

)_2023.JPG)